|

Stories

|

|

The 1910 Fire Eyewitness accounts from 1910 Fire Was the 1910 fire the largest? A Clash of Titans Relations of Forests & Forest Fires Could the 1910 fire happen again? |

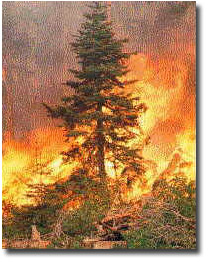

Where such forest lands have been protected from fire, as they are very largely through the progress of settlement, young trees have usually sprung up in great numbers under or between the scattered veterans which had survived the fires, and a dense and vigorous young growth stands ready to replace by a heavy forest the open parklike condition which the fire had created and maintained...

Where such forest lands have been protected from fire, as they are very largely through the progress of settlement, young trees have usually sprung up in great numbers under or between the scattered veterans which had survived the fires, and a dense and vigorous young growth stands ready to replace by a heavy forest the open parklike condition which the fire had created and maintained...