|

Stories

|

|

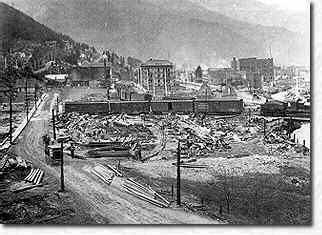

The 1910 Fire Eyewitness accounts from 1910 Fire Was the 1910 fire the largest? A Clash of Titans Relations of Forests & Forest Fires Could the 1910 fire happen again? |

W. B. Greeley grew up in California's Carmel Valley, the son and grandson of New England Congregational ministers. Except for Sundays, he spent his boyhood days exploring nearby woods, fishing and swimming in the Carmel River. The Sabbath was reserved for reading The Life of Christ, or a Sunday school lesson laid out for him by his father. Much later in life, he confessed to still having "a terrible New England conscience." He never smoked or drank and rarely swore.

W. B. Greeley grew up in California's Carmel Valley, the son and grandson of New England Congregational ministers. Except for Sundays, he spent his boyhood days exploring nearby woods, fishing and swimming in the Carmel River. The Sabbath was reserved for reading The Life of Christ, or a Sunday school lesson laid out for him by his father. Much later in life, he confessed to still having "a terrible New England conscience." He never smoked or drank and rarely swore.

In a 1911 report, Roscoe Haines, who was acting forest supervisor on the Coeur d'Alene National Forest, estimated more than 100 fires were started by coalpowered locomotives that frequently spewed red-hot cinders into tinder-dry forests. The railroad hired spotters to walk the tracks and douse flare-ups, but as summer wore on the inevitable drew near.

In a 1911 report, Roscoe Haines, who was acting forest supervisor on the Coeur d'Alene National Forest, estimated more than 100 fires were started by coalpowered locomotives that frequently spewed red-hot cinders into tinder-dry forests. The railroad hired spotters to walk the tracks and douse flare-ups, but as summer wore on the inevitable drew near.