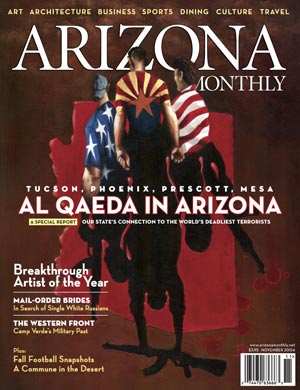

| Arizona Monthly | Nov 2004 | Al Qaeda Among Us |

|---|

Our greatest fears were realized when the 9/11 Commission report confirmed the presence of al qaeda in Arizona. But how did they get here?

Our greatest fears were realized when the 9/11 Commission report confirmed the presence of al qaeda in Arizona. But how did they get here?

By Len Sherman · Illustrations by Jason Moore There are 59 references to Arizona in the 9/11 Commission Report. But it tells only a fragment of the story when it comes to terrorists in the Grand Canyon State. A joint FBI-CIA analysis titled Arizona: Long Range Nexus for Islamic Extremists remains classified. Its existence was revealed for the first time when the 9/11 Commission released its final report this summer. But the long-standing link between Islamic terrorists and the Arizona desert has been in the public record for years–and it’s centered dead on Tucson, and in particular, the Islamic Center of Tucson (ICT). For nearly two decades, the most important nexus for international jihad outside of Pakistan and the Middle East has been Arizona. It’s not clear quite how or why the state has attracted what seems to be more than its fair share of individuals linked to terrorist organizations over the years. Experts have posited that the familiar desert climate; the anonymity provided by life in cities outside New York, California, and D.C.; and the easy access to a wealth of flight-training schools all played a role. But the most ominous explanation came from FBI agent Kenneth Williams, the author of the now infamous “Phoenix Memo.” In his testimony to a congressional committee in 2003, he said, “These people don’t continue to come back to Arizona because they like the sunshine or they like the state. I believe that something was established there, and I think it’s been there for a long time.” To be sure, the vast majority of the Muslims and Middle Easterners who have chosen to live or study in Arizona are decent, law-abiding people. The University of Arizona in Tucson, for one, has a long tradition of attracting people from the region thanks to its renowned science programs and the city’s quality of life. Since September 11th, however, U of A has seen a 54 percent drop in enrollment from the Middle East. The Center’s current leadership says the terrorists who have indisputably found their way to its gold-domed mosque across the street from a U of A dormitory and next to a Carl’s Jr. have nothing to do with the 8,000 or so Muslims living in Tucson. But that assessment is not universally shared. State law-enforcement agencies and the FBI have conducted numerous investigations in Arizona since the terrorist attacks of September 11th, and many of those centered on Tucson and the ICT’s well-documented, sordid history of attracting extremists. On November 19, 1999, two friends–both doctoral students, one from Arizona State University, the other from the University of Arizona–were driven to Sky Harbor Airport by a third friend in order to catch a flight for Washington, D.C.

The plane landed on schedule in Columbus, where local police officers entered the aircraft, handcuffed the students, and took them into custody. The authorities had been summoned by members of the flight crew, who found the students’ behavior strange at best, suspicious at worst. The FBI got involved as well as the local police, but the whole matter, as unpleasant and as ugly as it was, ended with the release of the students, who were not formally arrested or charged with a crime. They proceeded on to Washington, once again on an America West plane, and attended their conference. For their troubles, they sued the airline. That’s one way the story is told. Here’s another way. On November 19, 1999, Zakaria Mustapha Soubra drove Mohammad al Qudhaieen and Hamdan al Shalawi to Sky Harbor International Airport in Phoenix. The two men boarded an America West plane headed to Washington, D.C. with a stop in Columbus. On route to Ohio, al Qudhaieen got up and appeared to be headed towards the first-class bathroom. Though informed by a flight attendant that, as a coach passenger, he was supposed to use the bathrooms in the back of the aircraft, he proceeded to move to the front, where he was observed attempting to open the cockpit door on two occasions. He claimed to be looking for the bathroom. The crew was sufficiently alarmed that they asked the captain to contact the Columbus police, who were waiting when the jet landed. When the students eventually arrived in Washington, they attended a conference hosted by Imam Muhammad Islamic University, based in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, which sponsored their studies in the United States. Though the students later sued America West for “ethnic discrimination,” the case was dismissed by the court. At the time, the authorities could make neither heads nor tails of this, and the matter was dropped. But in the aftermath of 9/11, FBI analysts wondered whether this was a “dry run” for the attacks. It is now clear that Zakaria Mustapha Soubra–the two students’ driver to Sky Harbor Airport that day–was more than a student at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Prescott. FBI agent Williams interviewed him at his Tempe apartment in April 2000. This encounter, Soubra told the Los Angeles Times, was probably prompted by his visit to a shooting range with Abu Mujahid, an American-born jihadist who had fought in the Balkans and the Middle East. While in Soubra’s apartment, Williams noted a poster of Osama bin Laden on the wall and another of wounded Arab fighters in Chechnya. Soubra’s name was added to the U.S. State Department’s watch list one year later after intelligence indicated he may have received explosives and car-bomb training in Afghanistan. (The Soubra inquiry led to an investigation of six other individuals associated with him.) Soubra was also a leading member of a radical Islamic movement known as Al-Muhajiroun (the name of which translates to “The Emigrants,” a reference to the people who accompanied the Prophet Mohammed on his hijira from Mecca to Medina). It was this association that caused Soubra to be the “primary focus” of Williams’s “Phoenix Memo,” which tried to alert his superiors about Islamic extremists studying in U.S. flight schools. Al-Muhajiroun has its headquarters in London, and its web site asserts that its goal is to form a “fifth column” in Western countries for the purpose of penetrating “strongly in society and to become in position to overthrow the... kufr (infidel) regime.”

Speaking with counter-terrorist investigators, Bakri explained Soubra’s role: “he himself just supports al Muhajiroun, and effectively he becomes in charge [in Arizona].” It is still unknown whether Soubra played a part in September 11th, but one thing is clear: If the authorities had followed up on any of the leads developed by agent Williams, there may have been another outcome. If just one Saudi flight-school student had been picked up and interrogated, that might have led to a second student, with more questions asked and answered, and then the next student, and then the next. Pulling on that first thread could have pulled the entire cloth apart–but that first thread was never touched, and tragically, the plot remained intact. Bin Laden’s 1985 decision to leave his privileged life in Saudi Arabia at the age of 28 to take up jihad against the Soviets in Afghanistan has been much commented upon in the press. But the inspiration that sparked this radical move, the man who gave voice to bin Laden’s beliefs, has not received the same attention. Sheikh Abdullah Azzam, a Palestinian cleric who preached hatred for all Christians and Jews, long advocated worldwide jihad and the restoration of an Islamic empire. He was also bin Laden’s teacher at King Abdul Aziz University in Jidda, Saudi Arabia. Azzam moved to Pakistan at the start of the Soviet invasion in 1979 and set up the Mujahideen Services Bureau (also known as the al Kifah Refugee Center) to recruit and train fighters. The cleric eventually established dozens of al Kifah centers throughout the United States too, and its most important office after the one in Pakistan was found in Tucson. Bin Laden had become a central figure in Azzam’s organization by the end of the ‘80s, but his role was about to get much, much bigger. On November 24, 1989, a car bomb killed Azzam and two of his sons in Pakistan. Fundamentalists immediately blamed the Israelis, who surely had good reason to want Azzam dead. However, bin Laden and his right-hand man, Ayman Al-Zawahiri, have also been suspected of murdering Azzam, as the cleric’s demise allowed bin Laden to step forward and take control of the outfit, transforming al Kifah into an even more militant organization and a force with which the world would soon become all too familiar–al Qaeda. The terror network that would become al Qaeda has had scores of members living and working in Arizona during the past 25 years. The U.S. government is still sifting through information that spans decades, but the picture of bin Laden’s associates has been brought into sharper focus since September 11th. One of the earliest known preachers of jihad in Arizona was Wa’el Jelaidan, a Saudi cleric who co-founded al Qaeda with bin Laden. According to state corporation records, Jelaidan was the president of ICT from 1983-1984, during which time, according to a 2002 Washington Post article, “the mosque provided money, support and, at times, fighters to the forces resisting the Soviet occupation in Afghanistan, according to longtime members.” During his ICT presidency, Jelaidan also was a graduate student at U of A’s School of Agriculture and president of the university’s Muslim Students Association. However, he left Tucson in 1985 and turned up the next year in Peshawar, where he joined the Afghan resistance along with bin Laden and Azzam. In a 1999 interview with the Arabic-language news network al Jazeera, bin Laden discussed the founding of al Qaeda, saying, “We were all in one boat, as is known to you, including our brother, Wa’el Jelaidan.” On September 6, 2002, the U.S. Treasury Department named Jelaidan as a “specially designated global terrorist” and ordered his assets frozen after designating him as “a supporter of al Qaeda terror.” But perhaps most prominent among bin Laden’s early al Qaeda associates was Wadi el Hage, who eventually became his personal secretary. Born in Lebanon, el Hage was a Christian-born convert to Islam who studied at the University of Southwestern Louisiana before moving to Pakistan and becoming a mujahideen in the war against the Soviets. In 1987, he returned to the United States and moved to Tucson, where he was a regular attendee at the ICT. He made his living as a janitor, became a U.S. citizen in 1989, and stayed quite busy during his Arizona days. FBI agent Williams testified before a 2002 Congressional inquiry that “el Hage established an Osama bin Ladin support network in Arizona while he was living there, and this network is still in place.” El Hage spent the 1990s traveling between the United States and Africa, but his role in al Qaeda ended in 2001 when he was convicted in U.S. federal court and sentenced to life in prison for his role in the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Also noteworthy is the Arizona residency of Mohammed Bayazid, a Syrian-American who lived in Tucson in the 1980s and was suspected of being an al Qaeda arms procurer. Bayazid allegedly tried to purchase uranium in the early 1990s, and though he was subsequently arrested for his association with the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, it is unclear what became of him after that arrest in Mountain View, California. According to a 2002 affidavit, he was released under unclear circumstances and later fled the country. Today, Bayazid’s whereabouts are unknown, but he had a lot in common with Mubarak al Duri, an Iraqi native who also lived in Tucson in the late 1980s and who also allegedly tried to procure weapons of mass destruction for al Qaeda. The 9/11 Commission Report says al Duri traveled “as far afield” as China, Malaysia, and the Philippines but not whether he was successful in his search. The report does not document his activities in Tucson, either. Someone whose activities in Arizona have been very well documented, however, is Hani Hanjour, one of the hijackers who smashed American Airlines flight 77 into the Pentagon on September 11th. Hanjour moved from Saudi Arabia to Tucson in 1991 and enrolled in the University of Arizona when he was just 19 years old. He lived within walking distance of ICT, and authorities, as well as Hanjour’s family, believe he developed radically fundamentalist beliefs while in Tucson. In 1996, Hanjour began flight training in Arizona, enrolling in Scottsdale’s CRM Airline Training Center. He ultimately earned a commercial pilot certificate, issued by the Federal Aviation Administration, in April 1999. In the spring of 2000, however, he trained in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In early 2001, Hanjour and fellow hijacker Nawaf al Hazmi–who was in Central Asia with Hanjour from December 2000 to April 2001–trained at a flight school in Mesa, completing this phase of their education by the end of March 2001. The 9/11 Commission Report states that Hanjour also was associated with Rayed Abdullah, a radical Islamist from Phoenix, who received flight training too. Abdullah was a leader of the Islamic Cultural Center in Tempe, where, the FBI determined, he gave “extremist speeches.” Hanjour’s other radical, Arizona-based associates make up a considerable list, but one man in particular stands out: Ghassan al Sharbi. Al Sharbi attended training camps in Afghanistan, swore bayat (personal loyalty) to bin Laden in 2001, and was captured in March, 2002 in Pakistan. Al Sharbi also studied at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Prescott and leads us full circle back to the alleged 9/11 “dry run” on that America West flight in 1999.

The other America West passenger, Mohammad al Qudhaieen, was arrested by the FBI in June 2003, apparently in connection with the 9/11 investigation. He was released two months later and returned to Saudi Arabia. Soubra was denied a visa to re-enter the United States in 2001 following his alleged terrorist training in Afghanistan, but he was later allowed back in the country and was in Tempe when he was arrested in May 2002. Held without bond on a visa violation, he was ruled a national security threat and ordered deported. But federal agents blocked that order by obtaining a material-witness warrant and to keep him in custody, and Soubra testified before a federal grand jury under a grant of immunity. One year after being picked up, although never charged with a crime, he was deported to Lebanon. No one knows if or when terrorists will strike in Arizona, or anywhere else in America. What we do know is that our enemies will continue to try to live among us, attack us without remorse or quarter, and that this war will go on, beyond this year or next, generation after generation, on both the battlefields of distant lands and in the cities and towns of America. In a world of terror and fanaticism, shadows and lies, conspiracies and deception, this brutal, miserable reality is the one certain truth. |