| |

|

| < IMG Src=Ubull-bullet_lineup.jpg >

| An assortment of bullets, from left: Plated FP, Lead SWC, Lead RN, JSP, JHP, Jacketed RN

Pistol Bullet Basics

Understanding how bullets are constructed for each handgun shooting application is important background information for proper bullet selection, and to understand how the reloading process works.

|

| Construction

There are three basic types of bullet construction commonly used in handguns:

- Lead: Bullets that are solid lead. These bullets are cast, and offer specific ballistic characteristics, usually are lowest in cost, and are lubricated with a grease type of lubrication.

- Jacketed: Bullets that have a lead core, but also feature an outer jacket (usually copper) that engages with the rifling in the barrel of the handgun. These bullets cost more, can have greater accuracy, eliminate barrel leading (but do foul the barrel to some extent), and are approved for indoor use at local gun ranges.

- Other: Other types of bullets include plated bullets (thin metal coating), solid copper bullets, polymer coated bullets, and more.

Read on to learn what these acronyms mean.

|

|

| Application

There are two classifications for handgun bullets:

|

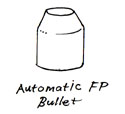

| Diagram: Automatic Pistol Bullet (Flat Point shown)

Automatic pistol bullets

Bullets for automatic pistols are typically plated or jacketed in composition. These bullets are also smooth on the sides, without special features for crimping. These bullets are held in place by neck tension (the press fit of the bullet into the case mouth, which is smaller in diameter). The shape of the bullet is optimized for reliable feeding.

|

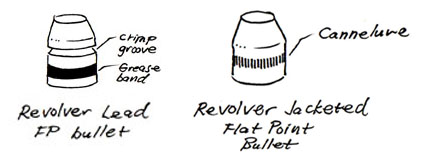

| Diagram: Revolver Bullets

Revolver Bullets

Bullets for revolvers are commonly either lead, or jacketed in composition. Revovler bullets have more variety than automatic pistol bullets because they do not feed from a magazine, and therefore have fewer constraints in composition or shape. Revolver bullets are held in place by a combination of neck tension, and a “roll crimp” where the mouth of the case is rolled over into the crimp groove (lead bullets) or the cannellure (jacketed bullets). Lead bullets have a band of lubricant around the sides to prevent leading of the barrel.

|

|

| Types of Bullets

There are many different types of bullets that each have a unique set of characteristics, and an intended use for each as well. Here, I’ll describe different types of bullets based on their fundamental shape and properties. Since acronyms are typically used to describe bullets (Such as RNFP for Round Nose Flat Point) I’ll cover the most commonly types of bullets, and leave it to the reader to understand other permutations of these terms.

|

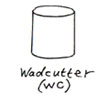

| Wadcutter (WC)

The wadcutter is perhaps the most basic bullet profile. Typically made from lead, these bullets are basically a cylinder of lead. These bullets produce clean “punches” in paper targets.

|

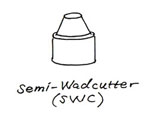

| Semi-Wadcutter (SWC)

The semi-wadcutter is a variation on the wadcutter. This bullet has a cylindrical body with a shoulder, and a flat point on the tip. These rounds offer better ballistic performance (less drag) than wadcutters, still punch nice holes in paper targets, and can be fed by automatic pistols in most cases.

|

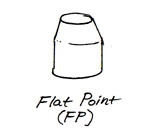

| Flat Point (FP)

Flat point bullets generally have a flat point on the tip, and a straight taper from the body to the tip. These bullets feed well in automatics, and punch a small hole in targets (the diameter of the flat point).

|

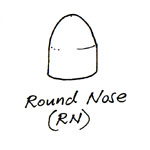

| Round Nose (RN)

Round nose bullets have a cylindrical body with a round tip. These bullets offer the best feeding characteristics for automatic pistols (Think ball 45acp ammo from WWI+, and 9mm parabellum) and good ballistic characteristics as well. These bullets do not punch clean holes in targets, and are not good for hunting and defense.

|

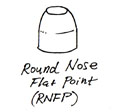

| Round Nose Flat Point (RNFP)

This bullet is a cross between the Flat Point (FP) and the Round Nose (RN) bullet with characteristics similar to the Flat Point (FP) bullet.

|

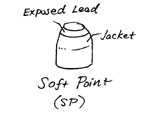

| Soft Point (SP)

Jacketed Soft Point (SP) bullets are a jacketed bullet with an exposed lead tip. These bullets offer the benefits of fully jacketed bullets, but with increased stopping power due to the enhanced expansion becuase of the soft tip.

|

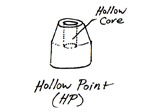

| Hollow Point (HP)

These bullets feature a hole in the tip which greatly enhances expansion and corresponding stopping power.

|

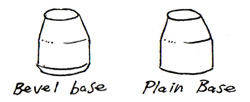

| Bevel Base and Plain Base Bullets

Another important characteristic of bullet shape is the base profile. Jacketed and plated bullets typically have a plane (flat) base. Lead bullets can employ a plain base (for increased accuracy) or a bevel base (to minimize lead shaving while seating, and to enhance bullet placement).

There you have it! The basics of handgun bullets. There’s much more to know, but this is enough to get one started in the reloading process. We’ll cover some of these topics in more detail in specific articles about reloading, bullet product reviews, etc.

|

| |

|

|

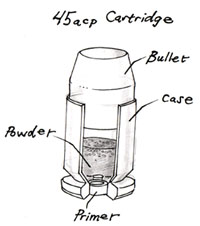

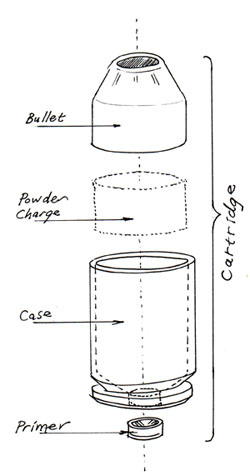

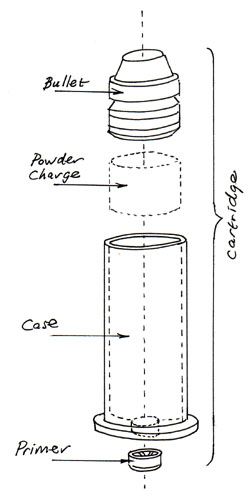

Pistol Cartridge Basics

Before we get into the process of pistol cartridge reloading, it’s important to make sure we understand the individual components that make up a completed cartridge. Automatic pistol and revolver cartridges are made up of the same basic components, but have some important differences we’ll discuss here.

Cartridge components:B

Shell casing

The shell casing (AKA “case”) is the core of the cartridge. If we were talking about a bicycle, this would be the frame. Shell casings contain the powder charge, hold the bullet in place, and house the primer which is used to initiate ignition. Shell casings can be made from a variety of metals, most frequently brass, but you will also find aluminum and steel casings.

Bullet

We all know the purpose of a gun is to send a bullet down range at a high velocity. Bullets have features that are particular to their use, and the type of gun they are used in. Bullets typically are made from lead, and some bullets have a copper jacket that encases a lead core. Some bullets are made entirely of copper.

Powder Charge

The powder contained inside the shell casing is ignited by the primer when the gun fires. The quantity and characteristics of the powder charge will determine the velocity of the bullet, the peak pressure for the cartridge, and effect things like accuracy and range. Selection of a proper powder and proper charge weights are very important considerations for safety and accuracy.

Primer

The primer is a small metal cup with a small quantity of high explosives packed in. The primer is pressed into the base of the shell casing opposite the bullet in a small area called the primer pocket. The primer is struck by the firing pin/hammer of the gun, causing a flame to shoot through the flash hole and ignite the powder charge. Spent primers (with indent from firing pin/hammer) are replaced during the reloading process.

|

Pistol Cartridge Types:

There are two fundamental types of pistol cartridges in widespread use today: automatic pistol, and revolver. There are really two main differences, the base of the cartridge, and the means by which the bullet is held in place.

|

| Diagram: Automatic pistol cartridge overview:

Automatic pistol cartridges:

Automatic pistol cartridges have a recessed groove around their base that is used by the extractor to eject the spent shell casing. The bullet is held in place by neck tension (where the bullet diameter is larger than that of the inside of the shell casing and is pressed into place). Automatic pistol bullets are typically jacketed, but you will some times find copper plated bullets (for lower velocity rounds, plating is much thinner than jacketing) and even lead bullets in some cases.

|

| Diagram: Revolver cartridge overview:

Revolver cartridges:

Revolver cartridges are held in place in the cylinder of the revolver by the rim on the base of the cartridge which is larger in diameter than the body of the shell casing. This prevents the cartridges from falling into the chamber, and is used to eject the shell casings or unfired cartridges from the cylinder. Revolver bullets are held in place by a combination of neck tension (where the bullet diameter is larger than that of the inside of the shell casing and is pressed into place) and a “roll crimp”. Roll crimping involves rolling the opening of the shell casing into a cannelure (for jacketed bullets) or a crimp groove (for lead bullets). By varying the ammount of roll crimp, the peak pressure of the cartridge can be controlled. We’ll get into more detail about bullets in another article.

|

| |

|

|

Pistol Reloading Basics

In this article, I will describe in simple terms the different stages that take place in the reloading process for pistol cartridges. Each stage corresponds to the common sequence and combination of events that occur for most turret or progressive style reloading presses with a common die setup. Note that order of these events, and even the combination of dies may vary from one process or piece of equipment to another. Reading this article will allow you to understand how this process works.

|

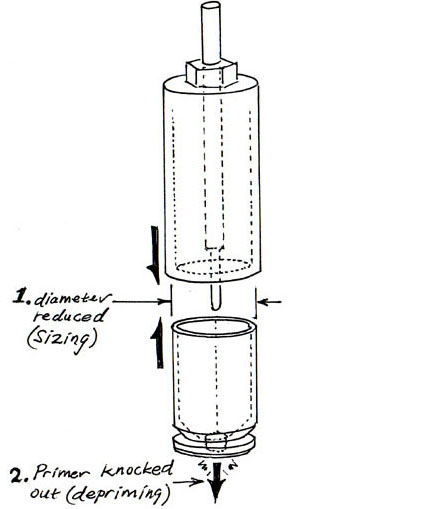

Diagram: Simplified view of sizing and depriming die in action Diagram: Simplified view of sizing and depriming die in action

Stage 1: Sizing and Depriming

The reloading process starts with used brass that has been cleaned. The brass expanded when the cartridge was fired due to the immense pressure pushing the brass against the chamber wall. Sizing the brass reduces the outer diamter of the brass down to the proper dimension. This will ensure that rounds will properly chamber, and that bullets will have the proper press fit (called neck tension) when seated. The second part of this first stage involves a decapping pin knocking out the old primer (pin enters through the flast hole and pushes on the primer). After this stage, we have a properly sized case without the spent primer.

|

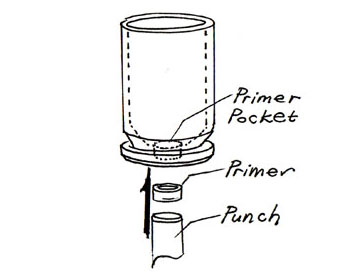

Diagram: Seating a new primer Diagram: Seating a new primer

Stage 2: Priming

After the brass has been sized and the old primer has been removed, a new primer is inserted into the case from the bottom. Typically, this involves a feeding mechanism positioning the new primer under the brass, and a punch then pressing a new primer into place in the primer pocket. Properly seated primers should be a few thousandths of an inch recessed into the primer pocket in order to ensure they can not detonate if the round is dropped, and to ensure proper feeding (automatics) or proper cylinder closure (revolvers).

|

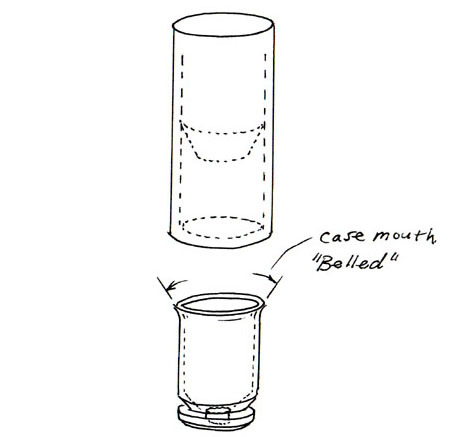

| Diagram: Simplified view of expanding

Stage 3: Expanding

After the case is primed, the case mouth is expanded or “belled out” so that in a later stage, the bullet can be placed into the mouth of the case, and be held steady prior to seating the bullet. In the case of lead bullets, this expansion also helps prevent the lead or lube from being shaved off the bullet by the mouth of the case during seating.

|

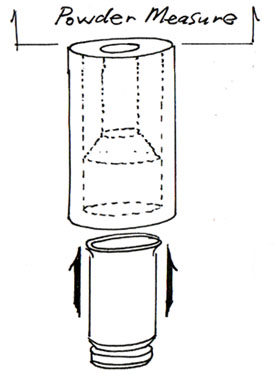

| Diagram: Charging the case

Stage 4: Powder Charge

Before you place and seat the bullet, the correct powder charge must be dispensed. Typically a device called a powder measure will measure out a predetermined volume of the powder you are using, and dump that powder down a “drop tube”. On some reloading presses, this is accomplished by the case pushing up on a podwder die (station), these arrangements are called case activated powder measures. The case now contains the proper quantity of gunpowder.

|

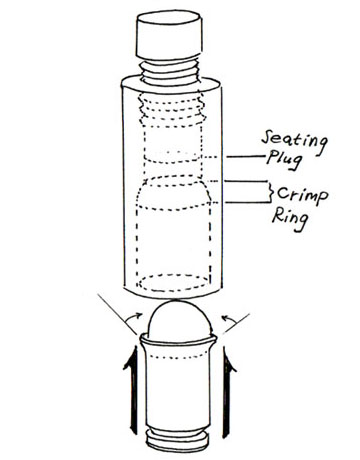

| Diagram: Seating and crimping

Stage 5: Seating the bullet, crimping the case

Once the case is charged with powder, we can place a bullet in the expanded mouth of the case. The bullet is then seated to a specific depth by the seating plug, which is lowered to an exact height. At the same time (for combo seating/crimping dies) the crimp ring roll crimps (for revolver) or taper crimps (for automatic pistol, shown here) the case.

|

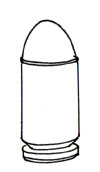

| Diagram: Completed Round

The completed round is properly sized, has a new primer, a charge of powder, and a properly seated bullet. The case has also been crimped so that the bullet is properly retained, and so that rounds chamber properly.

|

| |

|

|

|

Pistol Powders

|

Gunpowder Basics Gunpowder Basics

Proper selection of gunpowder is important for any realoading application. The various characteristics of the powder will influence the ballistics of the completed round, the consistency of metering, and many other things. In order to select a powder for your application, it’s important to understand the various characteristics that different powders exibit.

Powder Parmeters

There are a few characteristics that are most important to consider when choosing a powder:

Burn rate

The burn rate of the powder will greatly affect the peak pressure generated by the powder charge, and is important to match to the type of load (standard -vs- magnum), the bullet weight, and other factors. Typically, non-magnum loads utilize faster burning powders, where magnum loads utlilize slower burning powders.

Density

The density of the powder will determine how much bulk there is for a given charge weight. Bulkier powders can be helpful to prevent double charges (if one charge takes up most of the powder space, a double charge will either overflow, or not allow the bullet to seat, halting the ram before it reaches the top).

Granule shape

Each gunpowder particle is called a granule. The shape of the granules are a part of how the powder is manufactured, and will impact burning characteristics, and metering. The following is a list of common powder granule shapes.

|

| Ball powder

This type of powder consists of spherical granules that are typically small in size. This type of powder usually meters well.

|

| Flattened ball powder

This powder is very similar to ball powder but is flattened slightly. This type of powder behaves almost identically to ball powder.

|

| Flake Powder

This powder has granules that are shaped liky tiny disks. Flake powder can be more difficult to meter correctly due to the fact that it can “stack up” in the powder measure, and can be less uniform in density when metering.

|

| Stick Powder

This type of powder is most frequently used in rifle applications. Stick powder has granules that are shaped like small extruded cylinders. One issue that can arise with stick powders is the powder measuring cutting the sticks.

|

| Some common powders, from left: Winchester W-231 (flattened ball), Winchester W-296 (ball), Alliant Blue Dot (flake), Alliant Unique (flake)

|