A Firearms Primer

by Columba

Why guns?

The most common and most practical reason people arm themselves is for simple self-defense. A firearm is a powerful equalizer and the proper use of one is the most effective way to survive an attack by a run-of-the-mill street thug (the ones without badges). Such attacks are not common, but if attacked, your life - and the lives of those with you - are often on the line. In my view, this completely justifies the habit of carrying a firearm at all times.There are a variety of other reasons to invest in firearms. The Constitution recognizes that a citizen militia is the ideal organization for national defense, and such a militia requires armed citizens. Hunting for food in emergencies or on a regular basis is best done with a firearm. Hell, knowing how much it irks your local blissninny politicians could easily be motive enough to purchase a weapon.

When everything else is pulled away, the bare fact is that firearms are both tools and symbols of individuality and self-reliance. The person who goes armed acknowledges a responsibility for their own safety and demonstrates that their life, liberty, nor property will be taken from them without a struggle.

Gun Safety

Considering that the primary purpose of a gun is generally to kill something, it should be clear that guns are dangerous objects when handled improperly. The rules of gun safety are vitally important - they should become basic instinct, to the point that you find it deeply uncomfortable to violate them, even intentionally.

- RULE I: ALL GUNS ARE ALWAYS LOADED

Many people have been shot with guns they "knew" weren't loaded. Never make that assumption! Treat every gun as if it were loaded. Don't do anything with a gun until you have personally verified its status by opening the bolt or slide and looking to see if there is a cartridge in the chamber. - RULE II: NEVER LET THE MUZZLE COVER ANYTHING YOU ARE NOT WILLING TO DESTROY

Pointing a gun at yourself, your friends, your pet, or passing strangers isn't a joking matter. Doing so is just begging for a negligent shooting. This rule applies regardless of any safety devices on the gun. Safeties can malfunction. - RULE III: KEEP YOUR FINGER OFF THE TRIGGER UNTIL YOUR SIGHTS ARE ON THE TARGET

When the gun isn't pointing at your target, keep your trigger finger extended flat along the side of the gun. This will prevent you from firing accidentally (if, for example, you are startled by a sudden noise). - RULE IV: BE SURE OF YOUR TARGET AND BEYOND

You are wholly responsible for any damage done by a bullet you fire, regardless of what you intended that bullet to do. If you are unsure about what you are shooting at and what is behind it, don't shoot. Every year there are numerous incidents of hunters killing people and pets because they didn't bother to verify what they were shooting at.

These rules should be so ingrained in your behavior that they become second nature. I find myself instinctively keeping my finger off the 'triggers' of power drills, spray bottles and anything else with a gun-like grip. When I'm practicing with Airsoft weapons (pellet gun replicas of real firearms) it takes a conscious mental effort to point one at a member of the opposing team. This may seem like overkill - but I can picture few things worse than negligently shooting a friend, so I take them very seriously.

Types of firearms

All firearms use the same basic mechanism: a burning powder creates a large volume of gas behind a solid projectile (bullet). This gas is contained within the gun's barrel, creating very high pressure, which accelerates the bullet to a very high speed. In a modern gun, the powder, detonator, and bullet all reside in a single self-contained cartridge. In older guns, each component had to be individually loaded into a weapon. Only two basic types of guns existed at this time - the single-shot muzzleloader (either rifle, shotgun or pistol), and the muzzleloading revolver. Around the mid 1800s, cartridge firearms were developed. As well as being a remarkable jump forward in ammunition reliability, cartridges allowed the development of several new types of weapons. Each type of weapon has some good and some bad qualities, and each one deserves some attention.

- Muzzleloaders

As the name implies, a muzzleloader is loaded from the front (muzzle) of the barrel. First a charge of gunpowder is measured out and poured down the barrel, then wadding and a bullet are pushed down on top of it. There are a variety of firing mechanisms for muzzleloaders, but for the purposes of this article we'll only consider percussion, which is the most modern. In a percussion firearm, the powder and ball are loaded into the barrel and then a percussion cap (similar to caps used in toy cap guns) is affixed over a hole leading into the rear of the chamber (where the powder is). The percussion cap acts as a primer - when it is struck by the gun's hammer it explodes and ignites the charge of powder, which propels the bullet out of the barrel. Weapons of this type are available as single-shot and double-barreled rifles and shotguns, single-shot pistols, and revolvers. Aside from being fun to use and interesting to collectors and period enthusiasts, these weapons are interesting primarily because of their legal status. Because they do not use cartridges, they are not considered "firearms" by Federal law (a few states have other rules, though). As a result, they are not registered and may be shipped between states without going through an FFL. This is a neat legal exemption, but it's ultimately not all that useful, as muzzleloaders are far outclassed by modern firearms. - Revolvers

Revolvers were the first single-barrel repeating firearms. They use a fixed barrel and a rotating (revolving) set of chambers. Each chamber is loaded manually, and then after one is fired the next one takes its place, until they've all been used. There are two types of firing mechanisms found on revolvers; single-action and double-action. On both types the cylinders are fired when the gun's hammer falls on the cartridge aligned with the barrel. A single-action revolver requires its user to manually pull back the hammer, whereupon pulling the trigger releases the hammer and fires the weapon. A double-action revolver can perform both tasks from the trigger. If the hammer is down on a double-action, the shooter needs only to pull the trigger, as this will first pull back the hammer and the release it. Alternatively, the shooter can manually cock the hammer, and the trigger will then drop it, firing the weapon.Both types have their own advantages and disadvantages. Shooting a double-action revolver accurately at medium or long ranges can be difficult to do without significant practice, as the triggers on these guns require a good deal of force (often upwards of 10 or 12 pounds) to fire in double-action mode. However, a single-action shooter must manually recock their pistol before every shot. For close-range, defensive shooting the double-action is superior, as it is simpler to use (especially under stress). Handily, that same double-action revolver can also be manually cocked for precision shooting. A double-action is usually the better choice for a beginner - they are more versatile and simpler to use than single-actions. Revolvers offer some advantages over semi-auto pistols. A revolver has fewer controls, and is easier to become familiar with. Because revolvers do not eject brass upon firing, they do not suffer from some malfunctions relatively common to semi-autos. If a cartridge in a revolver should fail to fire, the shooter need only go through the motions of firing again, and the next cartridge will rotate into place and be used. However, when a revolver does seriously malfunction (primarily if the cylinder becomes stuck and refuses to rotate) it can be very difficult to fix quickly. Finally, revolvers can more easily use a wide variety of ammunition (such as cartridges of shot) as their firing mechanisms do not rely on recoil force.

- Lever-action

Lever-action rifles were first developed around the 1860s, and became very popular in the United States in the latter decades of the 1800s. The idea was to allow rifles to be loaded with several cartridges and then fired repeatedly before needing to be reloaded. These rifles (as the name implies) were designed with levers that were thrown forward and back in between shots. The opening stroke would open the breech of the rifle and pull out the fired cartridge case, and the closing stroke would push a new round into the chamber and close the breech. Most lever-action rifles had a tube under the barrel to hold ammunition (between four and twelve rounds, depending on the cartridge being used).Lever action rifles are still very popular, as they are both inexpensive and can be had in quite powerful cartridges. Another advantage of lever-action rifles these days is their non-threatening appearance to many people. Among the general public an AK-47 may bring to mind images of Abdul the Heinous Terrorist, but a lever-action Winchester conjures up John Wayne, American Hero.

- Pump-action

The pump (or slide) action mechanism is similar to the lever action, although it is most common in shotguns rather than rifles. Instead of a lever, the pump uses a movable grip underneath the barrel to cycle the weapon. Slide it back to extract a spent round, and slide it forward to chamber a new one. Like the levers, these weapons generally use a tube the barrel to hold ammunition (the pump grip is mounted on this magazine tube). - Bolt-action

Bolt-action rifles came about in the late 1800s and were the first repeating firearms widely adopted by military forces. The principle behind a bolt-action is mechanically very simple: a sliding bolt is used to lock the breech of the rifle. A handle attached to the bolt is used to open and close it - to close the bolt is pushed forward and then rotated to lock into the rear of the chamber. This provides the strength to withstand the pressure of firing. After firing, the bolt is rotated and pulled open, pulling the now-empty case with it. Most bolt-action rifles use a box type magazine, in which cartridges are stacked on top of each other behind the chamber of the weapon.Bolt-action rifles are the most common type of rifle in existence today. They are slower to operate than automatic rifles, but their mechanical simplicity and reliability keeps them popular, particularly among civilian shooters who don't look for the high rate of fire demanded by modern militaries.

- Semi-automatic

Also developed around 1900, the first semi-auto firearms were handguns. They work by using a small portion of the gas pressure from firing to automatically eject the spent case and load a new one. This can be done in a number of different ways, but the principle is the same in nearly all of them. In rifles, the most common mechanism is to have a hole in the barrel to tap some of the gases, and use their pressure to force a piston backwards to open the breech of the rifle. After the bullet exits the barrel this gas pressure dissipates and a spring forces the pison forward again, loading a new cartridges and closing the breech.Semi-autos are now common as handguns, rifles, and shotguns. As rifles and handguns they usually use a removable box magazine, and as shotguns they usually use the same tubular magazine as pump shotguns.

- Fully Automatic

The jump from semi-auto to full auto is conceptually very simple (in fact, the first successful semi-auto designs appeared after the first successful full-auto ones). A semi-auto will cycle once and then be stopped. A fully automatic firearm will continue to cycle (that is, eject old rounds and load new ones) as long as its trigger is held down. Because of this conceptual similarity, many full-auto firearms can be rebuilt as semi-auto only with a few modifications. The same is theoretically true in reverse (modifying semi-autos to fire full-auto), but the designs that were well-suited for such conversion have been stomped out of existence by the ATF. Those that still exist are now illegal to manufacture, and command a premium when sold. Such conversions can be done with relative ease by a skilled machinist equipped with a good shop, but the news media's "ten seconds with a file" crap is, well... crap.

Cartridge Nomenclature

Cartridge identification can be a tricky business at first, as different designers use(d) different systems for naming their cartridges. The only piece of information universally in a cartridge's name is the approximate width of the bullet. Other information is sometimes included, such as the length of the cartridge case, the designer, the company producing the cartridge, and the type of cartridge. Really the only practical way to gain familiarity with cartridge names is simply by memorizing all the ones you can. This isn't as difficult as it may seem, though. Let's examine some common ones:- .45 ACP - This is a very common pistol and (less commonly) submachinegun cartridge. The ".45" describes the bullet width. The decimal indicates that the measurement is in inches (only inches and millimeters are used for this, and a .45mm bullet doesn't make sense). The actual diameter of the bullet in this case is .452 inches, so the name is accurate (this is not always the case). The "ACP," which is sometimes omitted, stands for "Automatic Colt Pistol" because this cartridge was designed in conjunction with a semi-auto pistol made by Colt.

- 9x19mm - This is another very common pistol and submachinegun cartridge. The initial "9" is for the bullet diameter and the following "19" is the case length. Because of its ubiquitousness, it is often referred to as simply "9mm." This cartridge was developed by Georg Luger, who named it the 9mm Parabellum because he used it in military pistols he was developing. It is still called this, and also "9mm Luger." All four names refer to the same cartridge, making it the most confusing one there is.

- .223 Remington - This is the standard US military rifle cartridge, and it is used in the M16, AR15, Mini-14 and other rifles. The ".223" indicates bullet diameter (in inches), and Remington is the company that first produced it. An alternate name for this cartridge is "5.56x45mm NATO," because it is 5.56mm in diameter, the case is 45mm long, and it is a NATO standard cartridge.

- .308 Winchester - This is a common battle rifle cartridge, and its nomenclature is very similar to the .223's. It uses .308 inch bullets, and was introduced by the Winchester company. It also has an alternate metric name, which is 7.62x51mm.

- .30-06 - This cartridge was used in US military rifles from 1903 into the 1950s. It's name is derived from its military designation - it uses approximately .30 inch bullets (.308 inch, to be exact) and was officially adopted in 1906.

- .45-70 - While this looks similar to the previous example, it's quite different. This cartridge was used extensively in single-shot rifles in the 1800s. The .45 is the bullet diameter (.458 inch to be exact), but the "70" stands for the amount of powder it was loaded with: 70 grains. This is a fairly common naming system for cartridges of that era. Others named the same way are the .30-30, .44-40, and .38-55. Sometimes another number was added, which would indicate the bullet weight (in grains). For example, .45-70-300. It is important to note that these powder weights apply only to black powder, not modern smokeless powder.

- .357 Magnum/.38 Special - despite the difference in their names, these two calibers both use .357 inch bullets. In fact, the only differences between these two cartridges are overall length (the Magnum is 0.135" longer) and strength. The Magnum (as the name implies) is designed to be loaded with significantly more powder than the Special (the Magnum can deliver up to double the kinetic energy of the Special). The practical result of this similarity is that the cartridges are one-way interchangeable - a Magnum can also fire .38 Special rounds, which can be very handy. Note that the opposite is not true - a .38 Special firearm CANNOT safely fire .357 Magnum ammunition (and because of its greater length, .357 shouldn't be able to chamber in a .38). An analogous situation exists with the .44 Magnum and .44 Special cartridges.

Federal Laws

The three key Federal gun control laws are the National Firearms Act (1934), the Gun Control Act (1968), and the 1994 Omnibus Crime Bill. Each one represents a significant infringement of the right to own weapons, and we'll look at each one in turn.National Firearms Act: Passed with the intent of reducing gang violence by attacking stereotypical gangster weapons (sound familiar?), the NFA was the first Federal gun control measure. The entire text of the Act can be found at http://keepandbeararms.com/laws/nfa34.htm. Its basic provisions are:

Silencers, machine guns (any weapon firing more than one shot per pull of the trigger), short-barreled rifles (any rifle with a barrel less than 16" long or with an overall length under 26") and short-barreled shotguns (any shotgun with a barrel less than 18" long or with an overall length under 26") are subject to a transfer tax. Any time one is transferred (sold, inherited, given, loaned, etc) the recipient must pay $200, receive the approval of their local (or state) law enforcement head, DA, or prosecutor, and submit to an intensive background check through the FBI (including a photograph and fingerprints). Such checks generally take several months, but can be internally delayed for upwards of a year.

Furthermore, the Act defines a category of "any other weapon" as (basically) smoothbore pistols between 12" and 18" in length firing shotgun shells. These weapons are subject to the same approval, background checking and registration as the other weapons covered by the Act, but the tax on their transfer is only $5. Finally, the Act requires all importers, dealers, and manufacturers of the specified weapons to obtain licenses, submit to records inspections by treasury agents. The initial drafts of this law would have imposed these regulations on all handguns, but loud protests (particularly from women's groups) prevented that, thank goodness.

The information contained in each NFA transfer is recorded in the National Firearms Registration and Transfer Record, and the owners of such weapons are required to have their paperwork with the weapons at all times. Violation of the National Firearms Act is punishable by a $10,000 fine and up to 10 years in Federal prison. Or by fiery death, if the ATF decides that it's out to get you. On a historical note, the murders of the Branch Davidians and Randy Weaver's family were all done under the pretense of arresting them for NFA violations. David Koresh was suspected of having bought a machine gun without paying the $200 tax, and Randy Weaver was charged with having a shotgun with a 17.75 inch barrel (he was later acquitted by a jury, for what it's worth).

Gun Control Act: Passed in 1968 in the wake of the shootings of Martin Luther King, JFK, and Robert Kennedy, this bill created our de facto gun registration by introducing the Form 4473. It was, of course, supposedly passed in an effort to reduce armed crime. For some odd reason, it dealt with a lot of items rarely ever seen in crimes. Huh. The ATF has the text of the law available at: http://www.atf.treas.gov/pub/fire-explo_pub/gca.htm (all 160-some pages of it).

Anyway, the primary effects of the GCA were to ban mail-order sales of firearms (which is why all interstate sales must now go through FFLs) and to ban the importation of any weapon the Secretary of the Treasury deemed 'not a sporting weapon' (I guess the Secretary of the Treasury was given some vast well of firearms knowledge by this law at the same time). As I said, it also created the Form 4473 to record all relevant information on each gun sold by a dealer and to forbid sales to a variety of 'prohibited possessors,' such as convicted felons, drug users, legal and illegal aliens, and anyone who has renounced their citizenship.

The Act also defines "destructive devices" as (basically) missiles, bombs, poison gases, mines, and any weapon (except "sporting" shotguns) with a bore larger than .50 inch. Such items are also subject to the $200 transfer tax, law enforcement approval, several-month wait, and extensive background check.

Assault Weapons Ban: Passed in 1994, the AWB was another measure purportedly written up to protect us from criminals. Its actual effect on crime has been (predictably) negligible. Its effect on Joe Schmoe the Lawful Gunowner, however, has been far from negligible.

The law prohibits the manufacture and importation (though not sale or possession) of "semiautomatic assault weapons" (which I'll define in a moment) and any detachable magazine capable of holding more than 10 rounds of ammunition. This is the sole reason why 15-round 9mm pistol mags cost $40 and up.

A "semiautomatic assault weapon" is defined purely by aesthetics. It is any semiauto, detachable-magazine-fed rifle with two or more of:

- a folding or telescoping stock

- a pistol grip

- a bayonet lug

- a flash suppressor or threaded barrel

- a grenade launcher

It is also any semiauto, detachable-mag-fed pistol with two or more of:

- the magazine well outside the pistol grip

- a threaded barrel

- a barrel shroud

- an unloaded, manufactured weight of more than 50 ounces

- a semiauto version of a full-auto firearm

Or (we're not done yet!) any semiauto shotgun that has two or more of:

- a folding or telescoping stock

- a pistol grip

- a fixed mag capable of holding more than 5 rounds

- the ability to use a detachable magazine

There are some other Federal gun-control laws in effect, but these are the major three. The others include (among other things) a lot of behind-the-scenes actions meant to make the lives and businesses of licensed gun dealers, shooting range, and gunsmiths as difficult as possible. The Feds would be thrilled to regulate the shooting industry out of existence without any more blatant bans. Please support your local gun professionals and legal activism groups.

Common Firearms

Here are some of the more common firearms you will encounter.Glock

The Glock was designed by an Austrian, Gaston Glock, as a police and military sidearm. The novel element of the Glock is its firing mechanism. Rather than using a hammer, the Glock has a firing pin like a rifle's. Pulling the trigger partway back pulls the pin back against a spring and pulling the trigger the rest of the way releases the pin, which is pushed forward by the spring and hits the primer of the loaded cartridge, firing the pistol. The advantage of this system is that it requires no manipulation of a hammer (unlike a single-action) and yet each trigger pull has the same weight (unlike a double-action auto). This aids training and makes accurate combat shooting much easier. The downside to the system (you knew there had to be one) is that the trigger pull of a Glock is both longer and heavier than that of a single-action automatic.

Glocks are made in a wide variety of calibers (9mm, .40 S&W, .45ACP, .357 Sig, and 10mm) as well as in full-size, mid-size, and compact models. Magazine capacity ranges from 10-round Klinton mags up to some huge 33-round magazines intended for the full-auto variants. Furthermore, Glocks are renowned for their reliability and durability. They are less prone to malfunction than most pistols, and are also more resistant to damage (be it scratching, denting, or corroding) than most pistols. Glocks are also easily spotted by metal-detectors, as are all handguns currently in use. When movies and media mention "detector-invisible ceramic Glocks," they are full of crap. Finally, safety is a paramount concern, as Glocks have no manual safeties. They have internal safeties and a safety lever on the trigger which ensure the pistol will not fire unless the trigger is pulled - but it will always fire when the triggers pulled (keep your finger out of the trigger guard when holstering!). All-in-all, Glocks make quite good automatic pistol for those who don't want to spend much time messing with their pistol. They are simple to become proficient with and simple to maintain.

1911

The 1911 is one of the most popular and most common automatic pistols in existence. When the US Army decided to adopt a new service pistol in the early 1900s, John Browning entered his model 1911 pistol into the running. It won, and it has become a classic weapon. It is a single-action automatic pistol, so its hammer must be manually cocked before firing the first shot (the slide cocks the hammer automatically for each subsequent shot, though). The original (and still most popular) version is chambered in .45 ACP and feeds from a 7 or 8 round magazine (10-round magazines are available as well). The military spec 1911s, with comparatively loose-fitting parts are quite reliable, and their tighter competition-oriented cousins can be very accurate pistols. The major advantages of the 1911 are a comparatively thin grip (often more comfortable to use than the wider alternatives), a light trigger (easily tuned by a gunsmith to the shooter's taste), and the feeling of having the same model of sidearm that Alvin York and Audie Murphy used.

The 1911 is and has been manufactured by a great many companies and several foreign nations. Some have been made that use double-stack magazines, and they can be had in several calibers beyond the normal .45 (10mm and .38 Super are the most common alternatives).

AR-15

The AR-15 is the semi-auto version of the military M-16/M-4 rifle. It was introduced during the Vietnam War and has become an immensely popular rifle. In its basic form it is chambered for 5.56mm (alternatively known as .223 Remington) ammunition, has a 16" or 20" barrel, and uses 20- and 30-round magazines. A myriad of other versions have been made, though, ranging from pistols to 14-pound and heavier target rifles. One advantageous element of the design is that the rifle separates into upper and lower receivers. The lower contains the trigger mechanism, magazine well, and stock and the upper consists of the barrel, chamber, and bolt. In order to change the essential aspects of the rifle, a shooter need only swap upper receivers. A single lower receiver can be used with 16" carbine uppers, 9mm uppers, or even a single-shot .50 BMG upper. This versatility is a major part of the AR's popularity.

The AR-15 is capable of excellent accuracy, and if properly cared for is quite reliable (if not maintained well it will fall victim to adverse conditions more quickly than other military-type rifles, though). In my opinion the major problem with the AR-15 is it's small 5.56mm cartridge. This is advantageous for the military because it allows soldiers to carry more ammunition and keep their rifles under control during full-auto fire. For individuals, though, full-auto is generally not available and the result is a pointlessly weak cartridge with limited range, compared to the assortment of .308 rifles.

SKS

The SKS is a semi-auto rifle chambered in 7.62x39mm. Most use a fixed 10-round magazine which is reloaded using stripper clips, though larger fixed magazines can be found and some rifles were converted to use detachable AK-47 magazines. They were designed in Russia (in 1946) but have been manufactured throughout the ex-Communist Bloc. The appeal of an SKS is it's price - these rifles are easily available for less the $200. The downside is that the SKS has poor sights and is generally mediocre when compared to virtually any other military-style rifle.

An SKS makes a superb car rifle - if you just need a cheap rifle for an emergency kit, the SKS is a good choice. For a serious shooting rifle it is noticeably lacking, though.

AK-47

Similar to the SKS in many ways, the AK-47 and its variants are the most common firearms in the world, some 70+ million having been made all across the world. AKs are semi-auto (full-auto nearly everywhere outside the US) and use the same 7.62x39mm ammunition as the SKS. They feed from 30- and 40-round magazines (there are some 75-round drums around, though). The AK has a well-earned reputation for reliability and durability - it may not be comfortable or particularly accurate, but it will fire when you pull the trigger and almost never break.

The new Soviet standard rifles are AK-74s, which use the same design but are chambered in a different cartridge, 5.45x39mm. Some imported AKs are also made in .223.

Choosing Your First Firearm

There is no best first gun, but I do believe there is a best first caliber: .22 Long Rifle. Also known as the .22 rimfire, .22 LR, or just .22, it's a small cartridge ideal for learning to shoot. It is a rimfire cartridge, and its very light recoil helps prevent novices from picking up bad habits. It's also the cheapest ammo available (Walmart will sell you 500 rounds for less than 20 bucks), which lets you do a lot of shooting (something essential to developing shooting skills).There are a huge variety of .22 caliber firearms available, and most will work quite well for a beginner. The best are the rifles and full-sized pistols (though a full-size .22 will usually be smaller than other full-sized firearms). Avoid the tiny defensive .22 pistols - they're generally uncomfortable to shoot and have lousy sights and triggers. The choice between a rifle or pistol for a first gun is probably best made by what you intend to shoot primarily; rifles or pistols. If you want to carry a pistol for defense, a .22 pistol is the best first gun. Otherwise, a .22 rifle would be a better choice, as it is a slightly more versatile tool to have around, and will teach you the basics of shooting just as well.

In the pistol arena, there are a number of good choices. The Ruger Mark II and Browning Buckmark are very popular semi-auto .22s, and the Ruger Single Six is a good single-action revolver. Which type is better? I would suggest that you stick with the one that feels the most comfortable in your hand. Any quality .22 will be fine for learning with as long as you practice with it, and you're likely to practice the most with a comfortable gun. However, if the complexity of an autopistol is something you don't feel up to dealing with, a revolver is definitely the simpler-to-use choice.

As for rifles, the choices are nearly endless. Any decent bolt, lever, pump, or semi-auto will be fine. Some people recommend against semi-autos for first guns, as they do give the temptation of using volume in place of accuracy. Still the antidote is simply to take your time and take each shot carefully. Some popular .22 rifles include the Marlin Model 60 (my personal favorite), Ruger 10/22, Ruger 77/22, and Winchester and Henry lever-actions. The older Mossberg rifles can be very good as well. Frankly, there are so many worthwhile .22 rifles out there that one could write a whole book on them. Talk to sellers, avoid guns with rust, obvious broken parts, and shot out bores (use a light and look down the barrel - after making sure it's empty - and if you can't see rifling, move on to the next rifle) and you should have no trouble picking up a fine training rifle for about $100.

Once you have learned the basics on a .22, then you're well prepared to start shooting a heavier rifle or pistol.

Basic Marksmanship

There are four major components to marksmanship: grip, sights, trigger, and breathing. Sight alignment and trigger control are the most critical, but all four must be understood to shoot well consistently.Trigger control is the ability to fire a gun without moving the sights off the target in the process. This is accomplished by applying smooth and steady pressure to the trigger until it releases the hammer. The key is to think of the motion as pressing the trigger, rather than pulling it. A quick or jerky yank on the trigger will invariably move the pistol in that instant prior to firing and the result will be a missed shot. A good trigger can make a lot of difference in how steady of a trigger pull you can make - the best triggers are consistent and clean. In other words, they require the same amount of force throughout the pull, as opposed to having sticky or gritty feeling points. Firing a really good trigger feels like snapping a thin glass rod - it doesn't move as you apply pressure, until it suddenly breaks and fires the shot. A poor trigger will feel more like snapping a green twig - as you put force on it, it bends and bends and then reluctantly pops.

The grip is very simple in concept but take a lot of practice to master. The idea is simply to hold the gun so that the sights line the up on the target. The problem, as you will discover in short order, is that those sights like to wiggle around all over the place! In fact, no matter how proficient you become, your sights will always move around while you try to hold the gun on target. Practice does shrink your 'wobble area,' but what is more important is to learn to predict the movement of your sights, so that you can pull the trigger when the sights are over exactly what you want to hit. This element of prediction is needed because of the time it takes for a command to travel from your brain to your trigger finger - if you tell your finger to pull when the sights are right on, you won't actually fire until a moment later, by which time your aim will have drifted a bit off.

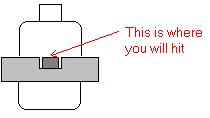

Sights are a two-piece system (unless you use a scope, which we'll get to in a moment) that predict a bullet's destination. The two parts have to be lined up in the correct way, or else the prediction is off (that is, you miss). The rule common to all iron sights (sights that don't use glass or optics) is that you should focus your vision on the front sight. This means that the rear sight will look fuzzy and the target will look fuzzy - and that's fine. It may sound weird, but it really does work. The way iron sights differ is in how they should look from the shooter's point of view when correctly aligned. I've draw a couple quick sketches of the correct setup for the most common types of iron sights:

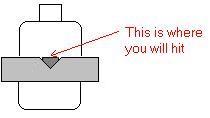

| Buckhorn sights consist of a v-shaped notch in the rear and a post in front. They're common to sporting rifles, which is unfortunate, because they are the most difficult sights to use accurately. On the ones with a shallow 'v', the front post should fill the 'v', and the top of the post should be on the same horizontal line as the top of the 'v.' Like so: |

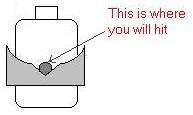

| On the deep-'v' buckhorn sights, the post is usually rounded off, and should sit in the bottom of the 'v,' like this: |

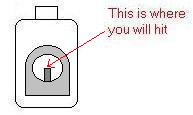

| A much better system is the aperture (also known as peep) sight. This system has the same sort of post in front, but the rear sight is a circular hole. Proper alignment is when the top of the front post is sitting right in the middle of the rear aperture. The neat thing is that your brain will tend to set the post right in the center unconsciously, allowing you to aim much more easily. A similar system is called the 'ghost ring.' It differs only in that the hole in the rear sight is much larger than on traditional aperture sights. This makes the ghost ring a bit faster to use and a bit less precise. Either setup should look like this: |

| The last major type of iron sight for rifle (and the primary type for pistols) is standard notch sight. It also uses a plain post in the front but has a squared-off notch in the rear. These sights are great on pistols, but leave something to be desired on rifles (and most surplus bolt-action rifles use these sights). They are aligned by placing the post level and centered in the notch, like this: |

Breathing technique is the least critical aspect of shooting for the novice, but is essential for anyone aspiring to become an expert shot. Your breathing effects how much your sights wobble (if you have a gun, try jogging or sprinting a bit at the range before shooting - the results might dismay you) so if you can slow down your breathing, you can make steadier shots. The most practical way to do this is to hold your breath while pressing the trigger. When I'm shooting at the range, my habit is to take full, calm breaths between shots, inhale deeply as I bring my pistol up to the target (or as I settle my rifle sights on the target) and then hold my breath as I press the trigger.

Another important skill in shooting is learning to call your shots. This isn't predicting where you'll hit before you fire, but rather knowing where you did hit before looking at the target. This is valuable because when you can do it successfully, it means that you are predicting your sight wobble correctly. Once you can tell with certainty were each shot went, you can see what you are doing right on the perfect shots, and make more perfect shots. In order to do this whole thing, you need to be able to see exactly where your sights were aimed when the cartridge fired. One habit that makes that much easier is to bring the sights back onto the target for a moment after each shot. Like the follow-through on a golfer's swing, this action can be surprisingly helpful in shooting accurately.

Glossary

Here are a couple terms I didn't get into in the article, but that are good to know.- Assault rifle - A type of weapon first developed by the Germans in World War II. It is a full-auto rifle that fires an intermediate round; larger than pistol ammo but smaller than rifle ammo. They offer a high volume of fire, and good accuracy out to a moderate range (a couple hundred yards). The two classic examples are the M-16 and AK-47.

- Assault weapon - A term legislated into existence and chosen because of its fearful sound. It generally means any gun that either looks like an assault rifle or is a mean-looking pistol. A couple of shotguns are included in the legal definition as well. These types of weapons are used in crime less than virtually any other type of firearm, and are the primary armament for legitimate citizen militias.

- Powder - There are two main types of gunpowder used to propel bullets. The older is called black powder, and is a mixture of charcoal, saltpeter, and sulfur. It is an explosive, and leaves a cloud of smelly soot behind when detonated. It was used in all muzzleloaders and some early cartridges, and generates relatively low pressures. In 1884 a French chemist developed modern smokeless powder. It is a more complex concoction, and burns cleanly (hence 'smokeless') and also generates much higher pressure. Interestingly, smokeless powder is not explosive - is simply burns very rapidly. In a cartridge, this has the same effect as an explosion - but loose smokeless powder will not explode if lit (it'll just burn up harmlessly). Do not ever use smokeless powder in a firearm designed for black powder - the higher pressure will invariably turn your antique firearm into an expensive pipe bomb (bummer!).

- Shot - Multiple round balls of a smaller size than the barrel they are fired from. Used in shotguns and (less frequently) pistols, shot spreads after being fired and creates a cloud of projectiles, allowing small moving targets like birds to be hit. Standard shot sizes range from #12 (0.05 inch in diameter) to #000 (0.36 inch).

- Submachine gun - A term for full-auto rifles that use small pistol cartridges. These weapons offer a high volume of fire but relatively low range and accuracy. Police forces tend to like these weapons, as the police use them in small areas like buildings where the range and accuracy limitations are largely irrelevant. They're also very popular with action movie stars. Examples would be the MP-5, Thompson ('Tommy gun'), and Uzi.

There are more issues involved with how to use and care for a new firearm that I can't cover here simply for reasons of length.

In the meantime, shoot straight and keep your powder dry!