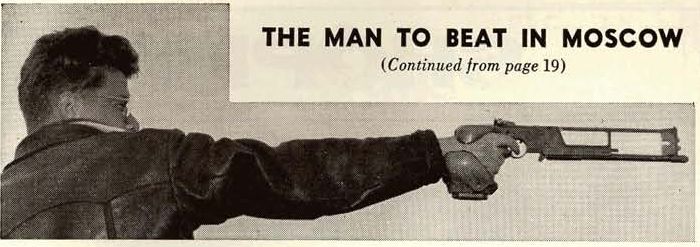

| THE MAN TO BEAT IN MOSCOW |

|---|

|

HE IS NOT A MARKSMAN, CANNOT EVEN SEE HIS GUNS

BUT IF SOVIET SHOOTERS WIN AGAIN HE WILL SHARE THE VICTORY

By VICTOR MARYANOVSKY

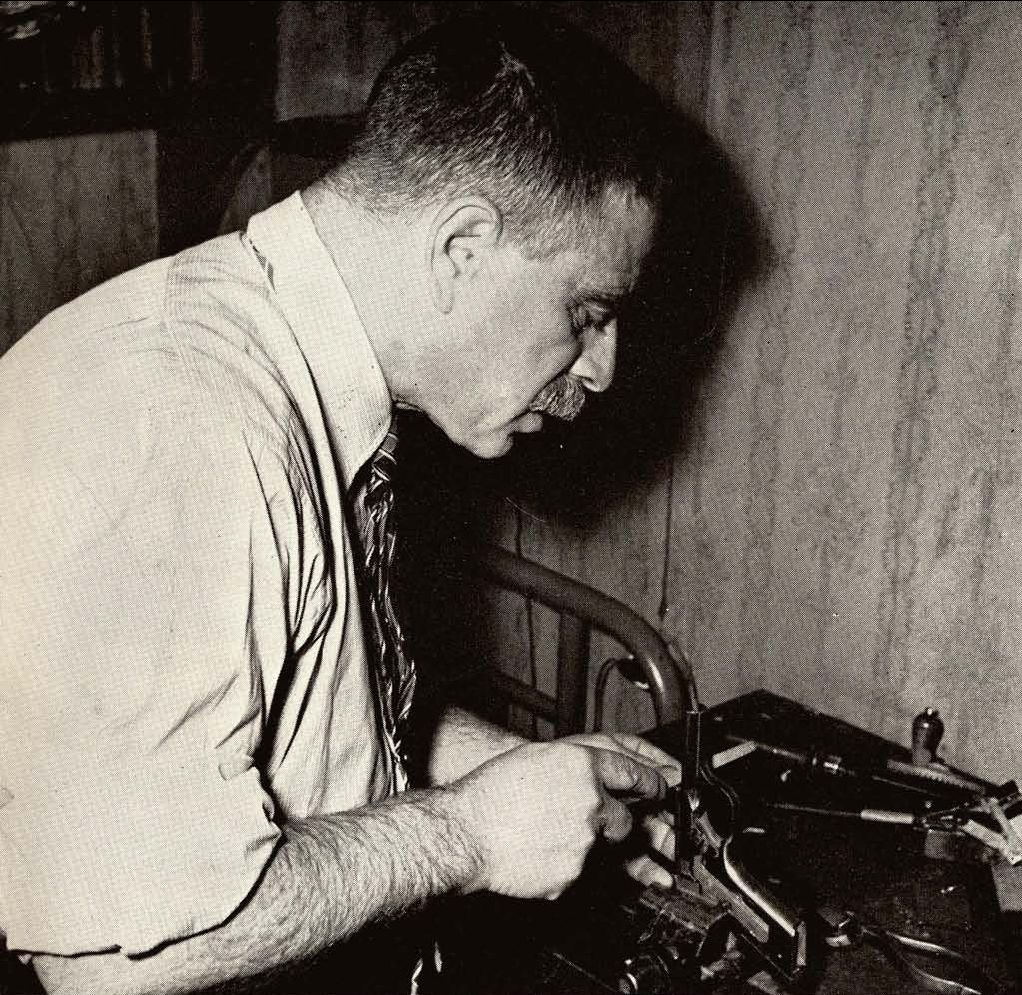

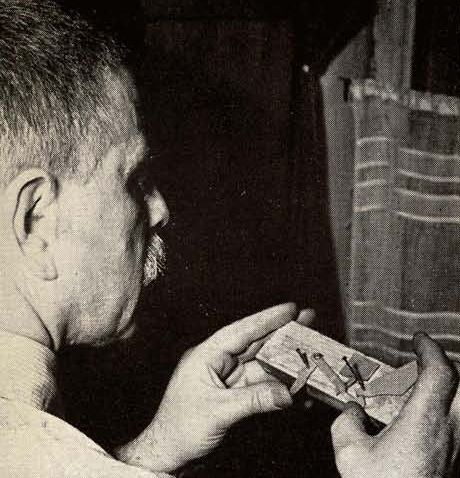

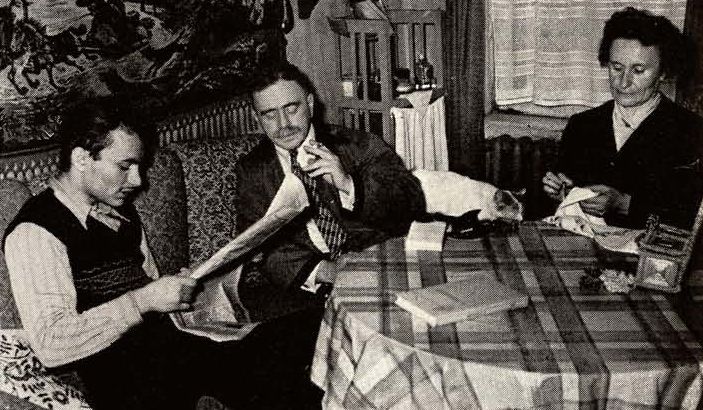

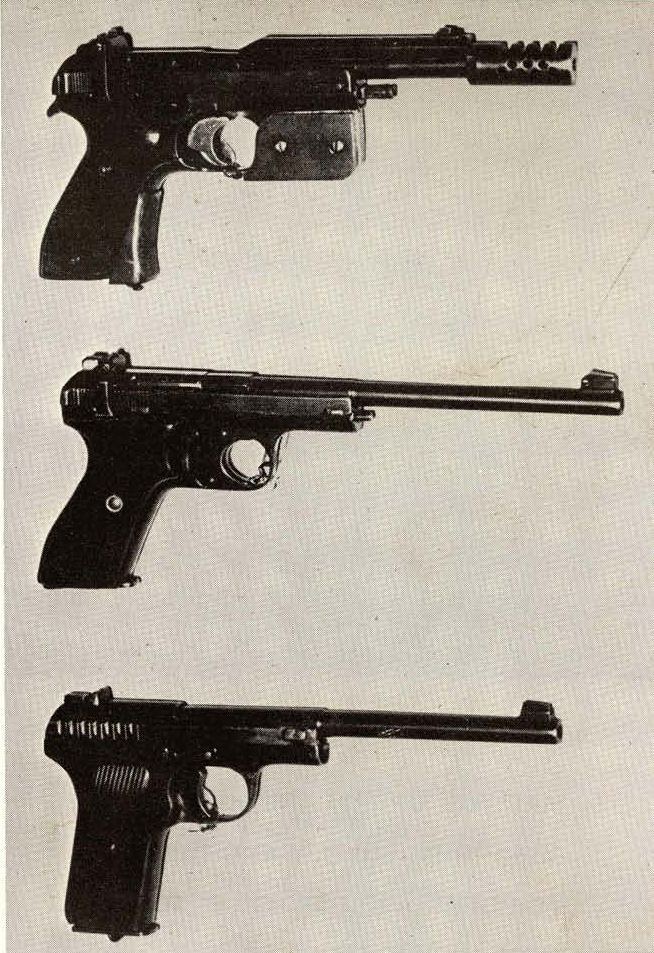

MOSCOW TARGET SHOOTERS are hosts this year to the marksmen of many nations. All are competing at the August, 1958 meet sponsored by the International Shooting Union. Western shooters will see many new Soviet sporting arms on the ranges. But new weapons will not be the only adversaries the visiting shooters must compete against, nor yet the sharp-eyed Soviet marksmen who have won honors in many countries recently. No, the man to beat in Moscow will not be on the firing line, except as an observer. And he will do little of that. For arms designer Mikhail Margolin, inventor of the fast-firing .22 which triumphed at Caracas, and of the upside-down pistol which created such a controversy at the Melbourne Olympics, is blind. He has never seen his guns. Margolin's career has paralleled that of the American, David M. "Carbine" Williams. Both worked under handicaps. Williams designed the .22 conversion for the U. S. army automatic: Margolin built a sub-caliber version of the TT33 Tokarev service pistol. Williams modified the Browning machine gun for .22 training: Margolin did the same with the Degtarev drum-fed Soviet light machine gun. The 10, 15, and 35 shot clips Mikhail made for the machine gun aided him in developing smooth-feeding magazines for his later sport automatic pistols, such as are now in the hands of Soviet pistol marksmen. Margolin's first international success came with the success of his pistol at Caracas, Venezuela, 1954, at the competitions for the world title in marksmanship. Rifle shooting had ended with a notable victory for the Soviet team, and small bore pistol shooting was about to begin. But many observers felt that would be the end of victory for the Russians -- they could not boast of great achievements in pistol competition; they had nothing to match the German Walther, or the American Colt, for rapid-fire shooting. Then Nikolai Kalinichenko took his place at the firing line. The first shot scored, and the next. . . . In two days of shooting, 60 shots, Kalinichenko scored 584 points, beating the world record set by Benner, the American. The team record was carried off by Soviet marksmen who scored 2,317 using the new pistol of Mikhail Margolin. Behind that pistol is quite a story, one I had to find out from Margolin himself. Visiting his apartment, I entered a small room. Ancient firearms hung on the walls, and there are books on the shelf. Next to it is a bed and a plain table. There is a small vise fastened to the table, and on it are files,little hammers, a brace and other tools. A stocky, graying man of 55 stands near the table, in his hands a small piece of wood with cardboard "parts" attached to it by nails. Margolin's fingers move carefully over the mechanism "watching" its inter-action. "Still too short," he murmurs and, putting the piece of wood aside, he picks up scissors and begins to cut a new piece out of thick cardboard, absorbed in his work. Margolin is a dedicated firearms inventor and when he talks, it is of those things which are important to him; his inventing, his designs. Margolin's enthusiasm for gun inventing developed shortly after a stray bullet during the Russian Civil War in 1922 plunged him into a world of darkness. Since then his passion for technology has grown stronger, sometimes amounting to an obsession. Margolin's hobby had been firearms, even as a lathe operator's helper at 19, and in service as a Black Sea sailor and as commander of an army platoon. During his service in the army he had handled various pistols, the Smith & Wesson, the Colt, the Nagant. He was familiar with the. designs to the minutest detail; now that he was blind, he often caught himself thinking of changing various parts of pistols, simplifying and improving their design. But there were days when Mikhail was filled with despair, not because his designs seemed too bold, but because he felt so helpless. He knew that among the blind were many renowned engineers, scientists, doctors. "Was there ever a blind designer?" he doubted. His schooling consisted of three years of elementary school and this knowledge, too, had been forgotten during the stormy years of the Civil War. But he did not stop with dreaming. First came the study of Braille. Friends helped him to study mathematics, mechanics and strength of materials, all essential subjects for the arms designer. His wife read aloud to him from textbooks and books on the history of firearms. He collected guns, enlarged his knowledge of various weapons systems. Most important was his splendid memory: within a few years he was a match for any engineer. As for firearms, there was no disputing his superior knowledge. He got acquainted with the latest models of weapons, took them apart dozens of times in order to let his sense of touch give rise in his mind to a mental picture. In the early thirties he started to design sports weapons. His first two pistols were failures. He thought of making a ten-shot self-loading rifle. The first model was crude. Unable to draw the gun parts on paper, he had to explain his ideas by gestures. A solution to Margolin's deep personal problem of communicating by his hands was found unexpectedly, at a sanatorium where the striving inventor had gone, depressed, to rest. He was bored by idleness. "Suppose you try clay modelling, that may be interesting," suggested his roommate. At first he worked on animal figures: elephants, tigers, horses. They were pretty good. And then he tried making gun parts in plasticine. It was an excellent idea, and turned his ideas into solid form. Then a vise appeared in'his room and he began to work with bits of aluminum and wood. or cardboard templates of mechanical shapes to check the principles of lock work and hammer-trigger assemblies. But it was a long time before he produced his first successful design, a semi-automatic sporting rifle. It appeared in 1934. The sporter was a smallbore autoloader with a demountable barrel and 10-shot magazine. The designer also progressed with a .22 practice machine gun using magazines of 10, 15, and 35 cartridges. As a result, a day came to Margolin of great honor, one which the most highly skilled gunsmith could be proud of. The blind man was invited to work at designing offices in the big government small arms factory at Tula, so noted through the centuries for its metal workers' skill that a Tula blacksmith, Levsha, is said to have shod a flea. There Margolin studied with Russia's greatest gun designers, Tokarev, Shpagin, Simonov. He continued to improve his favorite firearm, the .22 pistol. Designed at first around the military Tokarev pistol frame, Margolin's modification used a new 10" target barrel and a slide with forward limbs to compress the spring below the barrel. A cross bar held the assembly together somewhat like the old Colt M1902 .38 automatics were built. But Mikhail recognized this was only a start. He worked up numerous models, varying in grip angle, sighting arrangement and detail of slide construction. But all had the exposed barrel with the slide ribs below it, surrounding the recoil spring. Hammer and hammerless models were made. Finally a pattern seemed perfect, and the tests proved successful. The commission of experts recommend the manufacture of the first consignment of this new sport automatic pistol. This was on June 21, 1941. . . . On the following day, sport pistols were forgotten, as the first of Hitler's bombs dropped on the USSR's cities.

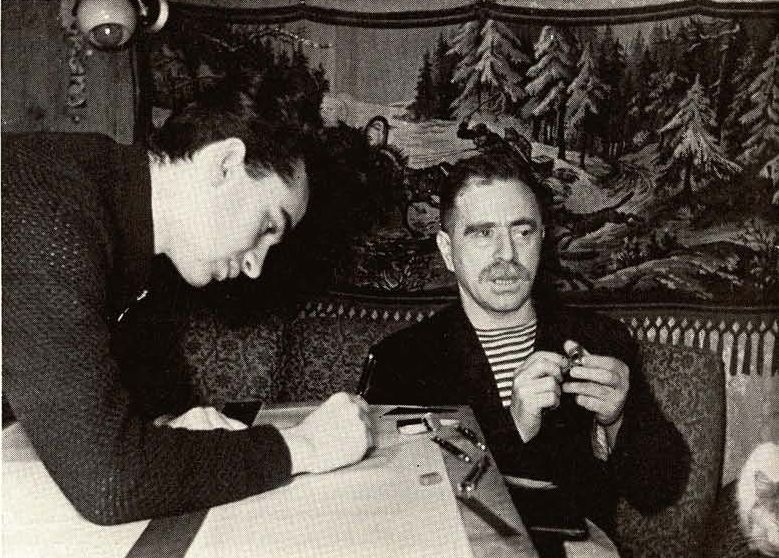

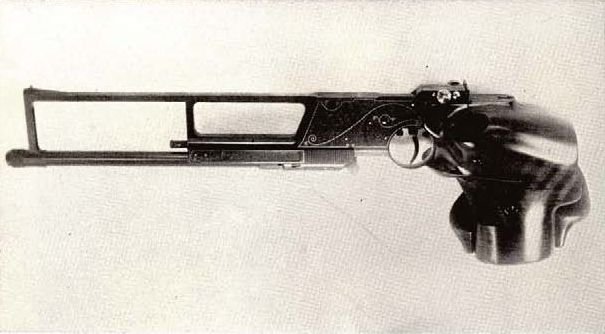

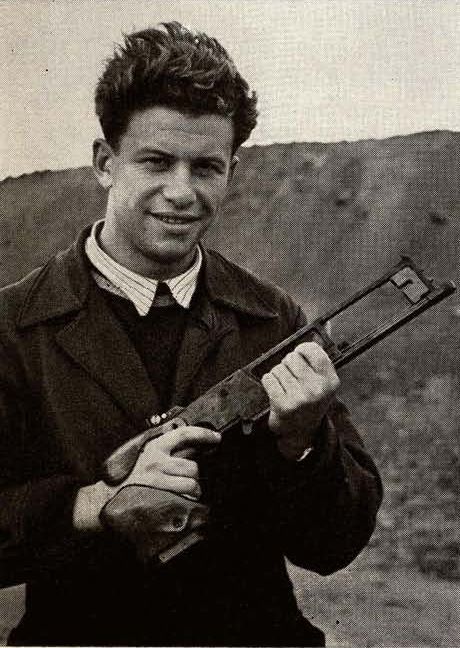

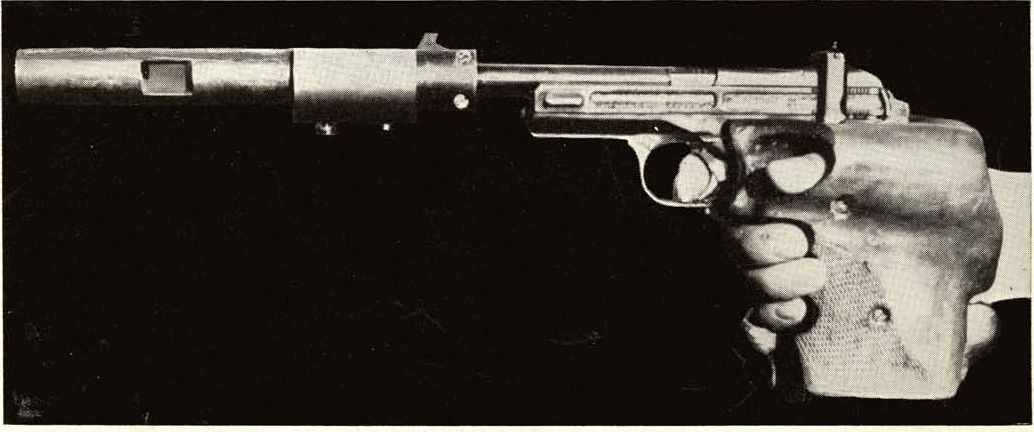

During the war Margolin worked as an ordance engineer. He developed many new ideas in design and manufacturing. His special knowledge of many types of arms was valuable and he took part in repairing trophy weapons. When the war was over, Margolin turned again to peaceful .22 pistols. And to the astonishment of his superiors, he scrapped the very design which had been recommended for mass production before the war. Within 18 months he had perfected an entirely new weanen which brought victory to the soviet sportsmen at Caracas! The new pistol had an important "first" in .22 target automatic pistol design, a nonmoving rear sight. Models made in 1946-47 have a rear sight bridge on the frame, through which the slide passes. The perfected pistol first hit the firing line at the USSR Shooting Championships in 1949. A 10-shot clip magazine blowback arm, the pistol had a new style of rifling, and the chamber was cut for 3.1 short case length as fouling difficulty had been experienced before in shooting the short cases in the long rifle chambers. The experience of the rifle clubs has shown that Margolin's pistol may be used for years. It will take more than 100,000 shots without losing its accuracy and unfailing action. The designer has equipped it with a muzzle brake and an adjustable thumb hole grip for any hand. From 1949 to 1954, the Russian team practiced. Then at Caracas, Venezuela, Kalinichenko eclipsed Benner's rapid fire International record and "Margolin's pistol" chalked up a team record. The title of world champion, dozens of gold medals, the Venezuela and Helsinki Prizes and the Lyons Cup were brought back to the USSR. But Margolin was not satisfied. Ahead lay an even greater challenge, the Olympics in Australia in 1956. He was preparing a surprise for the shooting world, the upside-down pistol. He keeps up with competitive design ideas. "The Americans, Norwegians and Germans have excellent gunmakers of their own," he says. "And of course they are always working on new ideas for sporting firearms. It takes some stepping to keep up with them." But in his new pistol, Margolin said: "I have made new calculations for the sight, changed the adjustable stock drastically and made the handle incline more convenient. There will be a new breech system and muzzle brake." The working drawings for the new pistol were prepared by Margolin through the help of his assistant, Kim Otomanenko, a young engineer. Their team work is rather interesting. Margolin dictates the drawings, using the models of mobile, fairly complex sections of gun machinery which he prepares himself. He makes them of cardboard, wood, metal, and some items are modeled of clay or wax. The designer and draughtsman have found a common, understandable visual language. The pistol which emerged was radically different from any firearm ever before designed in the world. Called the MTsZ-1, the five-shot competition 3.1 is built with the slide and barrel below the hand, the magazine feeding inverted from above. This caused the "kick" of the gun to strike downward, aiding rapid fire control as at the brieflyappearing targets of international silhouette shooting. The barrel lies level with the middle finger of the hand holding the pistol. The firing and functioning is regular blowback but the extraction and ejection of the fired case is positive even though gravity alone might accomplish this. The back sight has micrometer adjustable bobs, and both rear sight and front sight are replaceable. The trigger mechanism has regulating knobs for pull and weight. The handle is of a special shape to conform to the hand, and the newest models weigh between 2.75 pounds to 3.3 pounds. The first models had a fairly short barrel and only one strut from barrel to sighting line; later models used several different types of muzzle brakes and the perfected pistol has a long barrel with two struts holding the sight-line bar above the hand. The slide still has a cross bar for disassembly as in the earlier Margolin pistols. An elaborately inlaid and engraved example of this triumph of gunmakiig was exhibited in 1957 at a trade fair in Oklahoma in the United States. But it first met the eyes of other shooters, this pistol from the man who cannot see, at Melbourne in the Olympics. Evgenii Tcherkassov fired a Margolin pistol, as did Sorokiie. Neither took top honors but the Olympic committee was excited. So unconventional a design! As a result, the Soviet scores with the Margolin pistol, were approved at Melbourne, but for future shoots it was agreed that the rapid fire pistol must fit into a box 30 centimeters long, 15 centimeters high and 10 centimeters deep. Margolin's creation would not go into this Procrustean regulation and it has been banned for competition. But Margolin was not disheartened. Perhaps anticipating the action of the committee at the Olympics, he had begun to plan for the future, to think out a new pistol for international competition. Certainly the man who, as an air raid warden on duty on the roof of one of Moscow's big buildings, actually threw an incendiary bomb from the roof to the street where it burned harmlessly, and in the ruins of a lodging house demolished by bombs lead 120 old people, women and children to safety, does not lack for courage in the face of a little set-back. Banning his upside-down pistol has done only one thing to Margolin -- inspired him to develop new designs in sport automatic pistols. These will represent him on the firing lines at the International shooting competition in Moscow, will represent the target pistol designer who has never entered a match with one of his own guns, has never even seen them. |